If you’re reading this, you’ve definitely heard of cryptocurrency. Maybe you even own some! But perhaps you don’t know exactly where it came from or how it evolved.

Most people had never heard of cryptocurrency until Bitcoin started becoming popular a few years ago. Even the early adopters of Bitcoin way back in 2009 and the early 2010s may not have been fully aware of how this new technology that’s disrupting the entire world economy came into being.

For many people, it seems like Bitcoin—by far the most widely used cryptocurrency—just popped onto the random corners of the internet from nowhere. But, like most new technologies, Bitcoin wasn’t created out of thin air. When he created Bitcoin, Satoshi Nakamoto pieced together several important existing elements of cryptography and digital currencies that paved the way for the cryptocurrencies we know today.

Early cryptography

In the 1970s, mathematicians, engineers, and the government were working on cryptography systems that would make sending sensitive information more secure. Two independent cryptographers, Whitfield Diffie and Martin Hellman, solved a cryptographic key problem with public-key cryptography in 1975. They devised a way for two people who did not know each other to negotiate, with public observers even, and end with an encryption key that only they knew, using two keys: a public key and a private key.

Public-key cryptography revolutionized security because it eliminated the need for a trusted third party to provide a secret key. The NSA wasn’t particularly impressed with Diffie and Hellman’s work and claimed they would endanger the country by working on security without government trust. But Whitfield says, “Security is the science of minimizing trust,” including trust in the government. And that is one of the core concepts that drives crypto to this day.

The cypherpunks

Security continued improving using public-key cryptography, but as technology also advanced, new trust problems cropped up with the advent of the internet. By 1992, a group of cryptographers calling themselves the Cypherpunks created an email mailing list where they discussed their ideas and experiments in cryptography as they tried to solve information security issues. Among the members of the Cypherpunks were Julian Assange, Bram Cohen, who created BitTorrent, and many of the people who pioneered early iterations of digital currencies.

Security continued improving using public-key cryptography, but as technology also advanced, new trust problems cropped up with the advent of the internet. By 1992, a group of cryptographers calling themselves the Cypherpunks created an email mailing list where they discussed their ideas and experiments in cryptography as they tried to solve information security issues. Among the members of the Cypherpunks were Julian Assange, Bram Cohen, who created BitTorrent, and many of the people who pioneered early iterations of digital currencies.

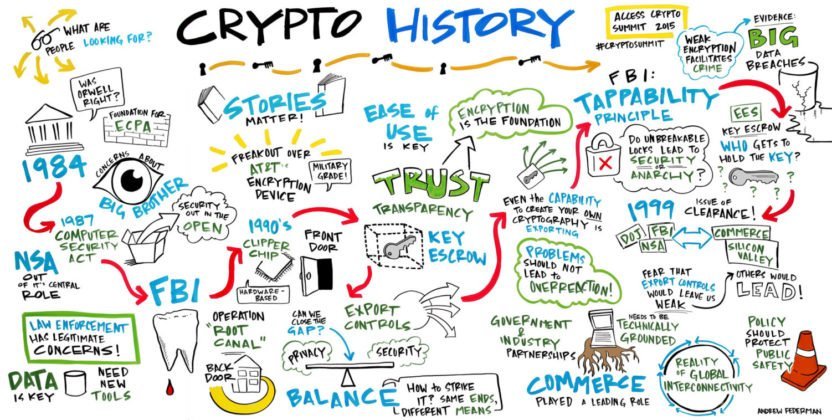

The Cypherpunks were concerned with privacy, having a strong distrust of governments and corporations, which are typically the gatekeepers of information and finances. These privacy rebels were not willing to give any ground to the government, even though exporting cryptographic technology was illegal and considered the export of munitions until the early 1990s. The argument over national security versus privacy became known as the Crypto Wars and, in many ways, it continues today.

Out of the ranks of Cypherpunks came a slew of coders who created important predecessors to modern cryptocurrencies. All of them contributed valuable pieces to the puzzle that Nakamoto solved with Bitcoin. Let’s talk about some of those solutions.

David Chaum and the double-spend problem

Once the internet was created, it was easy to dream up the possibility of digital currencies, especially with e-commerce becoming a huge enterprise. But in the early internet days, one of the problems with a digital currency was the possibility of double-spending. Meaning, if you had some digital money, it would simply be a piece of code. What would stop you from duplicating it and spending it in more than one place? David Chaum, a computer scientist at Berkeley, solved the double-spend problem for the first time with his eCash system in 1989. He used public-key cryptography to create a blind signature process to scramble, sign, send, and verify transactions, ensuring that eCash could not be double-spent.

Even though DigiCash, Chaum’s company, became popular and several banks licensed the eCash system, it never quite took off. Microsoft even wanted to integrate eCash into Windows, but they could never work out a deal with Chaum and, in the end, DigiCash failed. In addition to struggles with gaining adoption, there was still an issue with Chaum’s eCash system—it was centrally controlled by his company DigiCash. This did not eliminate the need for a trusted third party to be involved in verifying transactions.

Adam Back and proof-of-work

The next cryptographic evolution came from Adam Back in 1997 with Hashcash. The Cypherpunks were dealing with the new and growing problem of email spam. Because emails were easy to send, junk mail flowed into email inboxes with wild abandon. Back wanted to make sending mass spam email arbitrarily “expensive” so spammers would think twice before trying to send ads for “physical enhancements” and other unwanted communications.

Hashcash used something called proof-of-work, which necessitated the use of real-world resources to send an email. By attaching some public-key cryptography to emails, it would require computers to solve an equation before sending data. This would only take a couple of seconds and was not a big expense on a small scale, but those wanting to send out mass emails would have to expend much more computing power than they had.

The hashing process tied digital products, which alone are infinitely replicable, to the scarcity of real-world resources in the form of computing power and electricity. This “proof-of-work” placed consequential value on hashing. Hashcash, like DigiCash, did not gain mass adoption, but by putting a cost on information transfer, proof-of-work was the next step toward cryptocurrencies with real-world value and was cited in the Bitcoin white paper as a key component.

Wei Dai and distributed ledgers

By 1998, Wei Dai’s b-money solved a longstanding digital currency problem—the centralized ledger. In all of the so-far-attempted digital currencies, including eCash, the ledger was kept and updated by a central, controlling entity. This was diametrically opposed to the security interests of the Cypherpunks and anyone interested in freedom and privacy. Dai wanted a digital currency whose transactions could not be controlled or modified by a central power and which would be pseudonymous through blind signatures, allowing the ledger to be public.

With b-money, the ledger was distributed among all the users. Everyone would receive new transactions with blind signatures and update their ledger accordingly. Dai knew that b-money would not become ubiquitous and he was even a bit skeptical that cryptocurrency would ever be viable. Satoshi Nakamoto reached out to Dai before releasing the Bitcoin white paper but Dai did not respond. However, despite Dai’s skepticism, the distributed ledger was another important concept cited in the creation of cryptocurrencies. Not only that, b-money was tied to a basket of goods in the real world to stabilize its price. This functionality is also similar to what we know today as stablecoins.

Nick Szabo and smart contracts

Like several of the other Cypherpunks, Nick Szabo worked with David Chaum at DigiCash. There, he saw the problem of centralized digital currencies like eCash. He wanted to create an online safe haven where people could transact without trusted third parties, who he called “security holes.” Szabo considered property and contracts to be essential parts of society that were, unacceptably, enforced by the government. He wanted to create self-executing contracts that did not need trust. He even returned to law school in order to better understand contracts and is considered the creator of the smart contracts that are used in the crypto space today.

Szabo was also interested in free banking—a practice where banks created and issued non-sovereign (not issued by government) currencies. Competition in the free market would then determine which banks’ currencies would be most widely used. Free banking even existed in the US in the 1800s, but despite the currencies not being issued by the government, it still required the bank issuing the currency to be a trusted third party.

Bit gold, proposed in 1998, was Szabo’s solution to the centralization problem. He wanted to create a digital version of gold because gold has an independent value outside of simply being tender, like fiat. The idea for bit gold used hashing for proof-of-work and timestamping to determine the values of various hashes. Although bit gold was never implemented, the hash chain looked very similar to Bitcoin’s blockchain and some people speculate that Nick Szabo may actually be Satoshi Nakamoto.

Bitcoin finally makes crypto viable

On Oct 31, 2008, the Bitcoin white paper was sent out to a cryptography mailing list that was an unofficial successor to the Cypherpunk mailing list. In the paper, the pseudonymous Satoshi Nakamoto outlined a new idea for cryptocurrency that wove together multiple solutions from its crypto predecessors. It combined proof-of-work with consensus to create a mechanism that incentivized miners to mine bitcoins and maintain the server network. The blockchain was a distributed ledger that decentralized control of the currency. It also solved the double-spend problem by timestamping transactions. This, in addition to the longest chain always being taken as the valid chain, made double-spending almost impossible as proof-of-work ensured any attempt to modify the valid chain or extend a longer version would be essentially impossible.

Bitcoin also capped its supply at 21 million Bitcoins, which are mined at increasing intervals over time. Additionally, the decentralized issuance made Bitcoin trustless as well as inflation-resistant. Not only did Bitcoin solve many of the problems that previous digital currencies had failed to, it fortuitously came in the midst of the global financial crisis, which dealt a huge blow to public trust in centralized financial institutions. This opened the door for adoption in a way that no previous cryptocurrency projects had been afforded.

Cryptocurrencies gain momentum

Coders and crypto enthusiasts were among the first groups to begin using Bitcoin and as more people began mining Bitcoins, they also started trading them. In 2010, Laszlo Hanyecz paid for two pizzas with 10,000 Bitcoins. This was the first real-world purchase using the cryptocurrency and effectively set a price relative to the dollar. Assuming two pizzas were worth roughly $41, one Bitcoin would have been worth about $0.004.

Coders and crypto enthusiasts were among the first groups to begin using Bitcoin and as more people began mining Bitcoins, they also started trading them. In 2010, Laszlo Hanyecz paid for two pizzas with 10,000 Bitcoins. This was the first real-world purchase using the cryptocurrency and effectively set a price relative to the dollar. Assuming two pizzas were worth roughly $41, one Bitcoin would have been worth about $0.004.

Bitcoin’s decentralized nature made it pretty much impossible to control or censor. This opened the door for Ross Ulbricht and the darknet’s Silk Road, which allowed Bitcoin to be used as currency to buy and sell things on the black market. This marketplace lasted from 2011 to 2013, when Ulbricht was arrested. Julian Assange and WikiLeaks also used Bitcoin in the early 2010s to weather its US banking blockade, when WikiLeaks was ejected from centralized payment platforms.

Those paying attention quickly began to see the usefulness of Bitcoin and decentralized, trustless currency. It soon reached parity with the dollar in 2011—just a couple of years after its creation—and in the ensuing decade, despite wild swings of volatility, Bitcoin rocketed to a temporary all-time high of $64,899 in April of 2021.

Trading exchanges began to emerge thanks to the increased use of cryptocurrency, and in 2014, Mt. Gox was the largest exchange. However, it was investigated by the US Department of Homeland Security for not having proper registrations and it was also hacked, which resulted in the loss of 744,408 Bitcoins. By February 28, 2014, Mt. Gox was bankrupt, and many Bitcoin holders learned a difficult lesson about the importance of keeping custody of their crypto.

The crypto adoption explosion

With the accelerating success and adoption of Bitcoin, the shining example that cryptocurrency was viable, developers began working to expand the crypto space and create new currencies. While there are thousands of altcoins, the second largest cryptocurrency by far is Vitalik Buterin’s Etherum, which launched in 2015 and has since grown immensely because of its ability to use smart contracts more easily than on the Bitcoin blockchain. It’s also the main blockchain on which the decentralized finance (DeFi) ecosystem is exploding.

There are all kinds of altcoins, shitcoins, stablecoins, and memecoins in existence these days, using lots of different protocols and blockchains to varying degrees of success—and failure. Governments are also beginning to take notice of cryptocurrencies with attempts to regulate in some cases, adopting Bitcoin as legal tender in others, and now, most world governments researching the possibility of central bank digital currencies.

Conclusion

In just over a decade, Bitcoin has put cryptocurrencies on the map in a real way for the first time. But, as you now know, it was a pivotal, yet single step in the development of a larger, longer crusade by hundreds of freedom-advocating, decentralization-loving cryptography enthusiasts who saw the potential of a world with trustless, permissionless digital currency.

The origins of cryptocurrency began decades before when most people think it originated, and it will most certainly continue for decades into the future. No matter how technology changes and adapts to keep up with our modern, globalized world, the demand for security and privacy that can be traced back through time will remain consistent for as long as human nature drives power to concentrate in centralized, oligarchic attempts to control information and wealth.

About the Author

Michael Hearne

About Decentral Publishing

Decentral Publishing is dedicated to producing content through our blog, eBooks, and docu-series to help our readers deepen their knowledge of cryptocurrency and related topics. Do you have a fresh perspective or any other topics worth discussing? Keep the conversation going with us online at: Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and LinkedIn.